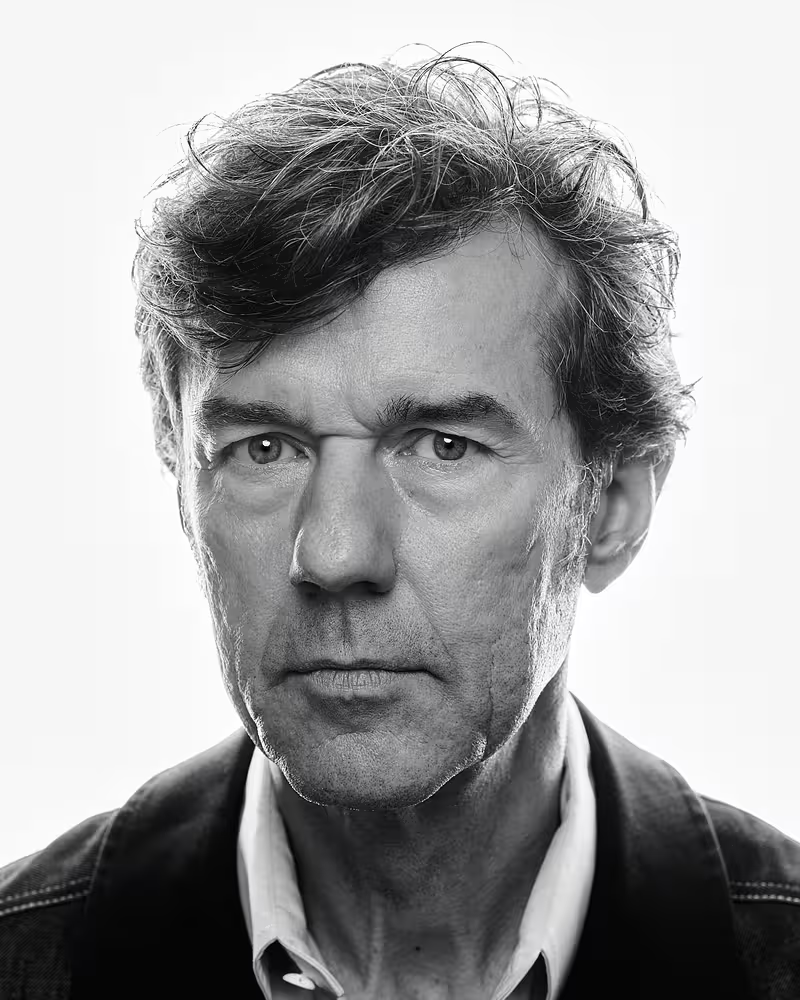

Stefan Sagmeister

Stefan Sagmeister formed the New York based Sagmeister Inc. in 1993 and has since designed for clients as diverse as the Rolling Stones, HBO, and the Guggenheim Museum. Having been nominated eight times he finally won two Grammies for the Talking Heads and Brian Eno & David Byrne package designs. He also earned practically every important international design award.

In 2008 a comprehensive book titled "Things I have Learned in myLife so far" was published by Abrams. Solo shows on Sagmeister Inc’s work have been mounted in Paris, Zurich, Vienna, Prague, Cologne, Berlin, New York, Miami, Los Angeles, Chicago, Toronto, Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul and Miami. He teaches in the graduate department of the School of Visual Art in New York and lectures extensively on all continents. In 2012 young designer Jessica Walsh became a partner and the company was renamed into Sagmeister & Walsh. A native of Austria, he received his MFA from the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and, as a Fulbright Scholar, a master’s degree from Pratt Institute in New York.

Talk: Design and Happiness

Stefan Sagmeister will explore the possibilities to achieve happiness as a designer, his tactics to make sure his work remains a calling without deteriorating into a job as well as the chances to design pieces that induce happiness in the audience. Lots of work from the last couple of years will be shown.

Transcription

[Futuristic humming]

[Futuristic music]

Audience: [Applause]

Stefan Sagmeister: Thank you, Marc. Thank you.

Audience: [Applause]

Stefan: Thank you very much to spend a nice Tuesday afternoon, evening with myself. I run a tiny design company in New York City. We are now 21 years old. We’re still only six people. Every seven years, we close the studio and try out, for a year, things that we don’t really have time or the wherewithal to explore when the studio is very, very busy, so a very classic sabbatical.

I found myself on the second of these sabbaticals in Indonesia and was doing furniture, not because I wanted to become a furniture designer. The studio is really centered on graphics. But, more because I thought it could be interesting and, in New York, we were renovating our place, so I needed furniture. I thought doing something that’s big, three dimensional, and out of my normal zone of operating could be an interesting thing.

One of my best friends came to visit to Indonesia, and he looked at all those one-to-one prototypes made out of cardboard that we had standing around. He says, “Well, this stuff that you’re working on is sort of interesting but, ultimately I think it’s a waste of your time.” I didn’t really want to hear this, but I had to somehow admit that he did have a point, that there might be something else out there that could be of more use to other people. I took a break from the sabbatical and thought of what that could possibly be that would be of more use to other people.

Before, I had given a talk on design and happiness, sort of kind of similar to this one, but somehow the friend and I thought, because that talk had always gotten very good feedback, I thought maybe I could do something on that subject. Making it a bit more challenging, not doing a book because it would have been easy, let’s do a film because I’d simply never done a film before. This was six and a half years ago, and there still is no film in sight.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: It turned out that making a film has much less to do with graphics than I hoped it would, and that it is even very difficult to make a bad film, that just because -- well, actually, maybe because I have good taste in films, because my sophistication as a viewer is extremely high and completely out of whack with my sophistication as a doer, it became an unbelievably unhappy to experience to make the film about happiness.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: On the way to this state, there were a couple of things happening. One of them was that the Institute for Contemporary Art in Philadelphia called us and said, “Do a design show for us,” and we already had a design show moving around or traveling around Europe, and it seemed a boring thing to create the same show again just so they could show it in time in Philadelphia. We said, or I said, “Why don’t we do a show about happiness instead?”

The said, “Well, possible,” and we went to Philly to look at their galleries. This was their small gallery, and then they had, at the ICA, one that was much larger, both basically classic, white cube kind of situations. It seemed nice. Then, as we walked into the galleries, I also asked them, “What’s the story with all these non-spaces like these staircases, these wheelchair ramps, or the elevators?”

The said, “Well, nobody ever does anything with them.”

I said, “Well, can we use them?”

They said, “Well, sure. Go ahead.”

With one single question, we doubled the square footage or the square meters available for us in the museum, and so these became the elevators.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: There were some freight elevators that opened differently.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: This was the wheelchair ramp where I cherrypicked my favorite research that I found by talking to psychologists. Ignored all the research that didn’t fit into my thesis but concentrated on the stuff that did. It’s a very popular way of dealing with science, even in science.

[Music]

Stefan: All of it, of course, was based on this question that I actually asked the question, “Can we use all the other spaces?” We made this little film about it, which is really the life motto of a friend of mine, of Richard Soul Wurman, who also founded the TED conference. It says, “If I don’t ask, I won’t get.” We’ll just pull up the volume and let it run.

[Music]

Stefan: You can turn it up a little bit. Yeah.

[Music]

Stefan: So, on a scale from zero to ten, how happy are you? Can we get some house lights on? Who feels like shit? Who is a zero?

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Nobody. Number two, who feels bad? Number four, who is bored? Five minutes into my talk.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: I can take it. I think there is a bored person up there or just scratching your nose. I’m not sure.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Things are okay, number six? A couple, 20. Then number eight, I feel good? All right, look at happy Berlin.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: I love life, number ten? All right. So, I would say, “Wow! Much happier than usual,” and I would say, “About 100 of you feel absolutely nothing right now.”

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: I knew this. There’s tons of international happiness research. I know that Germany is doing quite well. It’s at the very, very top of the happiness scales, but first always is Denmark and second is Switzerland. Now, I’ve spent a lot of time both in Copenhagen and in Zurich. If you’re in the pedestrian zone of either city, you don’t really feel that you have been surrounded by a particularly happy folk. Uh….

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: However, there is ample evidence of other factors. I think, in Denmark, most people think that things won’t work and are unbelievably surprised at the couple of things that do work and very thankful for them.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: I think, in Switzerland, there are incredible amounts of trust out there. School children in Switzerland answer the question, “Most people can be trusted,” by 85%, while in Rio de Janeiro it’s only 15%, which I guess makes a difference in perception. If I’m in Rio, I think the people in Rio are much happier than the people in Zurich, but there are other factors involved.

I’m actually super bored by definitions, but I’ll tell you one about happiness anyway simply because it’s such a gigantic piece of terminology. I think that, one, that’s a definition that I like is one that divides this giant word into lengths of time. You have tiny, short pieces of happiness, a moment of bliss, possibly an orgasm. You have number two, middle long things like satisfaction of well-being like lying on the couch with the paper and the dog. Or, you have very long kind of happiness like finding what you are excellent in, in life or just basically fulfilling your potential. Obviously, these three things have nothing to do with each other, but they are all under this big term of happiness unless, I guess, if you have an organism or fulfilling your potential are two very different things unless you work in the porn industry.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: If you look at it from a different point of view, activities play a giant role in our daily lives and, there again, nonrepetitive activities. The fact that you chose to listen to a talk on happiness on this Tuesday night was, from a pure psychology point of view, a fantastic choice, even if I’m terrible, simply because likely you didn’t do it yesterday, likely you’re not going to do it the day after tomorrow.

Number two, life conditions, all the big things. I’ll come back to it a little bit later, but if you’re rich or poor, black or white, all that stuff plays a surprisingly tiny role. The reason for that is because we get used to it and take it for granted.

Number three, genetics do play a big role, roughly half. But, because we can’t do anything about it, I won’t really get too deeply into it.

[Low tone ringing]

Stefan: The surprising thing is that even though I know that nonrepetitive activities are so important, which also means that spontaneity would be super important, I am actually not very good at it. Meaning, I am not a spontaneous person. I think a lot of success that the studio enjoyed actually comes from being focused and from being single-minded, but we haven’t really done much spontaneous stuff. Even Jessica is much better at being focused and single-minded.

As a reminder, we made this little thing for the show called Be--and you’ll see it in a second--More Flexible. This piece was made by a young motion graphics guy from Argentina who came to the studio for a couple of months and did it. That’s all digital as opposed to, let’s say, the little film that we saw before with the balloons that was all shot in camera. There were no digital effects going on at all, while this is all digital effects. There was no camera involved in this soap bubbles.

Men are as happy as women are. Climate plays no role. The shittiest climate in the United States, Buffalo, New York, people are as happy as they are in Santiago, the best climate in the United States.

Income is super interesting. In the U.S., until $85,000 a year, money plays a giant role. If you are super poor, you are unhappier than if you are, let’s say, middle class. But, $85,000, what’s that, 60,000 euros, 5,000 euros a month is, in the U.S., basically a middle-class salary. If you’ve reached higher than that, your happiness factors do not change. This is from last year giant Gallop survey; 650,000 people participated. This is not some little university thing. The differences above $85,000 were not measurable, which is surprising considering how many people outside and in here, how much energy we spend to go from $85,000 to $185,000.

White people are as happy as black people. Older people are a little bit happier than younger people, but not by much. Ugly people are as happy as super pretty people. Down here, it starts making a difference.

If you are very sociable, meaning if you have a lot of friends and if you have good friends, you will be happier than if you are a loner. And, if you are religious, you’re going to be happier than if you’re nonreligious. There, strangely, the more religious the better. The more fanatic, the better.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: The sad part is that religious fanatics are very happy people.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: And, married people are happier than single people.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: I’m not a fanatic, I’m not religious, and I’m not married, so I have ways to improve my own happiness levels.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: For the show, we had a nice advertising budget, so we had these buses going around, which led to pretty good audience members or visitor numbers. We so far had over 0.25 million people visiting the show, and they stayed 5 times as long as they would normally do in a museum show. We had a little piece of sausage as an invite.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Becoming fat is one of the nice pieces of happiness. These are some shows, and here it’s more important. This is one of the many, many, many books that I read about the subject written by Jonathan Haidt. The reason that I thought this was excellent was because it still was a holistic overview of happiness but, at the same time, coming from a very scientific point of view. Everything that he says is backed up by data.

This is Jonathan. I called him up, and it turned out that his wife was a designer artist, so he actually knew who I was. We got together and became friends. He kind of served now as a scientific advisor both to the show as well as to the film.

Maybe the most startling thing for me in his book was that he, in the book, stated very clearly in his opinion there are three strategies that are most effective if you want to elevate your wellbeing, if you want to become happier. Number one, meditation. No problem. Back to Bali, I went. Three months of meditation.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Number two, cognitive therapy. There’s a ton of cognitive therapies right there in New York, and I went for the first time in my life to see a shrink. Number three: drugs. I kept the easiest one for last.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: This is not illegal drugs. I had taken plenty of illegal drugs before and I know which ones worked and which ones didn’t. It didn’t seem to be that interesting. These are legal drugs as in pharmaceutical. In my case, it was Lexapro or a Prozac related drug, an SSRI.

Jonathan talks in the book about the conscious mind and the unconscious mind like a little rider. The conscious mind on a giant elephant, the subconscious mind. The two ride along, and the rider thinks he can tell the elephant what to do and clearly where to go, but the elephant really has his own agenda. It is only through proper training, as in meditation, in cognitive therapy, or with pharmaceutical drugs, that the two can learn how to work together properly because the theory by Jonathan, but also by other big psychologists, is that if you can get the conscious and unconscious to work together that really would be a full life and you would make good decisions.

Now, I looked at some U.S. data. If you see a guy whose name is George who doesn’t quite know where to live--Florida, Nebraska--somehow Georgia sounds best to George. Then if you see a guy whose name is Dennis who doesn’t quite know does he want to become a doctor or a lawyer or a teacher, somehow dentist sounds best to Dennis. Paula is unsure who she should marry, ultimately decides for Paul.

Even though we all think that we make these decisions, these big decisions of our lives ourselves, if you look at the data, there are more Georges who live in Georgia. There are more Dennises who become dentists. And, there are more Paulas that are married to Paul than would be statistically viable.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Now, when I saw this data, I thought, well, “These stupid Americans. Uhh!”

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Somehow are dangled around by their elephant, by their subconscious, in ways that clearly the rider doesn’t understand. They make these giant decisions on something as flimsy as the sound of the name being similar.

I looked back at my own family. This is my mom, Karolina, marrying my dad, Karl.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: And, my grandma, Josefine, marrying my granddad, Josef.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: I was engaged once and tried to talk my fiancée into changing her name into Stefani. Unsuccessful.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Emotions, there are six of them, six basic emotions.

[Piano music]

Stefan: You can see what a fantastic actor I am here. I think this is sadness. This is joy.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Disgust. Surprise. Anger. And, fear.

If you paid attention, six basic emotions. Only one of them is positive: joy. Everything else is either neutral or negative. That leads to a negativity bias, meaning that we actually are more open to negative things than positive things.

The reason why every attempt to make a positive news organization failed within weeks because we are not interested. It’s not the media to blame. The media would be super happy to give us all positive news all the time if that’s what we wanted. I know it for myself if I look at a blog that talks about my work. I can look at a hundred positive comments, but I’m definitely zooming in on that one negative one. It’s just so much juicier somehow.

I actually do know why this is so. My brain contains the amygdala that allows fear to go through much, much faster than joy. If I see something scary, my mind realizes the scariness before my eye has a chance to send back the information to the proper parts of my brain. My stone-age ancestors, of course, they really had a lot of fears that threatened their lives, so evolution had a lot of reason to pull fear way up. But, you know, I lead a very quiet life, and I’m sure that I would benefit if I would somehow be able to risk more.

Number two, a term from psychology: presentism. If you’ve ever been to the supermarket, you came in hungry, and you bought too much stuff, you know what presentism is. On a more serious level, if you or a friend that you know has ever been depressed, the reason we have such a difficult time to snap out of depression is that we can only see our own point of view from this very moment, and we have a very, very difficult time to see the world in a different way either from somebody else’s point of view or from another moment.

Please pick one of these cards and remember it.

Back to the happy show. We had a button in the wall. You pushed the button. Out of the wall, a card came that gave you one instruction on what to do next in the show. There were 50 different cards, 50 different instructions that many, many people followed.

One of the instructions was this one. It had my cell phone number on it, so I got many, many, many, many jokes.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: It also worked a wonderful little counter of how many people were in the show when the show was in Paris, and I got ten jokes. I knew there must have been a minimum of 500 people in the show that day.

In the States, all of the jokes were like this. They were all super child-friendly, very cute jokes. I was only when the show traveled to Europe that they became a little bit more existential.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Back to the cards we go. Remember the card that you picked?

Audience: [Chatter]

Stefan: I removed it from this lineup.

Audience: [Chatter]

Stefan: Yes?

Audience: Yes.

Stefan: All right. Not just a graphic designer, but also a magician.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: But, I can tell you how I did this. I exchanged all of the cards.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: But, likely, if you’re like me, you only remember the card that you picked and ignored the surroundings.

Audience member: (Indiscernible)

Audience member: (Indiscernible)

Stefan: Very much like I did with you in the beginning of this talk. We measured the happiness levels of the visitors to the show with these chewing gum machines. This is after two weeks in Philadelphia, you see they are pretty much sevens in Philadelphia. This is after two weeks in Toronto. Clearly, Canadians are much happier than Americans. And, this is after six weeks in Toronto.

We also had some type made out of sugar cubes saying, “Step up to it.” The sentiment itself came from my shrink. There was a projection on the sugar cubes. The projection knew if the viewer, if the visitor, was actually smiling. There was a hidden smile detector software in there.

As you looked at the sugar cubes and you actually smiled at the sugar cubes, the sugar cubes became colorful. You can see right here, you see people smiling for the sugar cubes. The visitors noticed that this is happening and smiled on purpose for the sugar cubes. Of course, smiling is contagious, so we had a pretty good mood in the large gallery in Philadelphia.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: So, three things. When I talked to Jonathan in the very beginning about what is it that I could do in addition to make myself happier, he said, “Well, this is all about a skill as well,” and we had here a big list on the computer. I was actually surprisingly good at many of the things that he thought would be important if you want to elevate your wellbeing.

But, when we went through the list, there were three things that I thought I wasn’t that great on, and so this was stuff to work on. Number one was thankfulness. I really have never been such a particular thankful person. For example, at talks like this, I never thank the organizer. I just think it’s a little bit boring and most of the times when I hear speakers thank the organizer, it always seems somehow insincere, so I’m going to change that tonight. Is Marc around?

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: You want to thank the guy and then he is not here.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Oh, Marc! Are you around?!

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Can we call him together?

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: One, two, three -- Marc?!

Audience: Marc!

Stefan: Are you around?!

Audience: [Chatter and laughter]

Stefan: Well, we might get him afterward anyway. In any case, I actually do mean it. It’s a total pain in the ass to organize such a thing. It would be a complete nightmare for me to do, like nothing worse for me than organizing a conference, doing all the thankless tasks, then rebooking speaker planes.

I think, in my case, not that I made him rebook my flight, but there were just constant annoyances of the travel agent thinking that the flight changed, but it didn’t. There’s a lot of aggravation in organizing something like this. I think he’s doing a particularly great job. So, wherever you are, Marc, thank you very much.

Audience: [Applause]

Stefan: And, thank you’re the chocolate.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Number two, too big to talk about, a giant field, we actually just had a long discussion about it in front of a camera today in the afternoon.

[Birds chirping]

Stefan: Part of the meditation, part of the exercises that I did in Bali was about that. We did make a piece.

[Music]

Stefan: I think there’s still a ways to go for me, but we did make a piece about it where it says, “Feel others feel,” and every letter has fluids on top of a loudspeaker, and every letter influences the other letter next to it, and every word influences the words on top of it.

Then, three, humility, I don’t really give a shit about.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: I know a whole bunch of people who are not humble, and I love them dearly, so that one I think I’ll leave alone.

We also had a little box asking people to draw a symbol of happiness. No smiley faces allowed. There was obviously a lot of feedback. We got a number of symbols, but we never really knew what to do with them. Then only in Paris, we just changed the wording slightly and said, “Draw an animal that you think is doing well.” That, just a change in wording, completely changed everything, and we got thousands and thousands of these animals that people thought were doing well.

[Music]

Stefan: And so, we could do this for hours, the animals going by in a parade that people in Paris thought are in a good mood.

[? Happy, happy, joy, joy … boy, boy. The disco… ?]

Stefan: You get the picture.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: You get the picture. If you want to draw your own animal, just make a little sketch, do it digitally, or make a little sketch, take a photo of it, and send it to hello@thehappyfilm.org.

We also had bananas on the wall, a lot of them in different kinds of ripeness. The green bananas spelled out “self-confidence produces fine results” on a bed of ripe bananas. A week later, that confidence completely disappeared.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Two weeks later. Three weeks later. Four weeks later. Five weeks later. Overall, of course, in that whole timespan, you had quite a pungent banana smell. Uh!

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: In those galleries and outside, a piece of very long typography over 200 meters long saying, “Worrying solves nothing,” dividing these coat hangers, a street that had a lot of fashion stores inside. That’s one of the sentences that I’ve actually mastered quite well. I’m not a big worrier anymore, or at least at night when something comes into my mind that I’m starting to worry about, I’m just pressing; I’m just ignoring it, and I picture myself, instead, in a super warm, cozy truck driving through a very, very cold climate, mostly Siberia. See, I bring all my sausages all the time.

Outside, there might be all kinds of crazy stuff happening like bad guys or so, but I’m super safe in my truck, and I always sleep in, in the process. I don’t really have a solution for whatever I would worry about, but I get a good night sleep and can properly worry about it the next morning.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Let’s look quickly at this one example of that hand-picked research. Let’s say if we look at companionate love versus passionate love, if you look at it from a six-months point of view, passionate love is so much stronger. It’s so much more exciting. Companionate love, that little friendship love looks like it’s pretty weak down there.

But now, if you zoom back and you look at the whole thing from a 60-year point of view, passionate love looks like what it is, a flash in the pan, while the companionate love really has a chance to grow. This is from Jonathan Haidt. Basically, he says that when he interviewed couples that were married 40 years or longer, it was always companionate love, friendship love with a little bit of passion mixed in.

He actually says that it is biologically impossible to be passionately in love for longer than six months because the dopamine levels that are associated with it are extremely unhealthy for my body, and so it has to come down. Otherwise, I would lead an extremely unhealthy life. The only couples where you see dopamine levels extended for more than six months are couples where one of the partners is not available, meaning married to somebody else or living in Japan.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: I also figured out in my experiments that it’s actually more -- it makes a bigger difference in my day if I exercise 25 minutes in the morning than if I meditate for an hour. I wanted to have some sort of exercise vehicle in the show, so you have this bicycle. If you peddle long and hard enough, you are generating the electricity that powers a piece of neon typography in front of it that says, “Actually doing the things that I set out to do increases my overall level of satisfaction.”

You can see it now when the camera comes around. “Actually, doing the things that I set out to do increases my overall level of satisfaction.” I really do believe that if I think, “Oh, I really should do that,” and then I don’t do it, it leaves that little piece of residue in my brain. If I do it again and again and again, these pieces of residue form a little ball of discontent that ultimately does have an effect on my life.

If today or tomorrow any of the speakers say anything that triggers something in you that says, “Oh, I really should do this. I should try something in that direction or this direction,” instead of letting that go, I urge you to take out a little notebook, write it down, and then, in the next break, figure out a reasonable timeframe for this thing. Just put a deadline on it and put it in whatever calendar system you use. Then--that’s super, super, super important--keep that time as absolutely holy because I can tell you and guarantee you that you want to be able to change that time.

The reason that is, is because, I can tell you from my perspective, there’s a lot of stuff that I want to that I know I want to do and I told all my life that I want to do them. But, when I actually want to do them, and they are new, they are unbelievably difficult to do. They’re actually much more difficult to do than the stuff that I have to do for my clients because the stuff that I have to do for my clients, I normally know how to do. The stuff that I don’t know how to do turns out to be much more difficult. Then I always have the excuse, “Oh, I can’t really work on that thing that I said I’m going to do, to myself, because I have this other stuff for my client that has a deadline attached to it,” or there is always some email crap to do, or all this or that.

In my case -- I can’t speak for you. In my case, there are total excuses. It’s just that it’s more difficult. Just in this very, very same vein that the most I’ve ever procrastinated in my life ever was on the happy film. The most time I spent, “I think I should work on the film now,” but did not work on the film, was definitely my own personal project.

I longed to be able to do a logo. It was so much easier. It’s simply because I’ve done countless logos in my life and I found it easy to do countless logos. I found it super difficult to write this voiceover for the film that I don’t really know what I’m going to say, and I don’t really know how to write the voiceover.

If there was anything today, do it.

[Traffic noise]

Stefan: At the very tail end of Bali, I also found a repeatable way to create an artificial moment of pleasure.

[Music]

Stefan: Here’s the recipe. Take a scooter. Find a road that doesn’t have a lot of traffic on it, so you can ride without a helmet, so the wind goes through my hair. Puts ten songs that I can reasonably expect I’m going to like on my MP3 player, but don’t know too well. Then, super important, have no plan. There is no agenda. I don’t have to drive anywhere, and just riding around for the simple pleasure of riding around. Every single time I did that, I had goosebumps going down my spine, so basically a physical mood of a moment of bliss.

Whenever I had a plan, meaning, whenever I said, “Oh, why don’t I do it?” but I have to go there, it did not work. Even when we filmed this, it didn’t work simply because we went out to shoot it, so there was a reason. There was a cause to do that. There was a function to the whole.

Realizing this, we then ultimately made a little piece for the Chicago show that said, “Uselessness is gorgeous,” made out of little cigarette papers and a couple of fans in front of it. The idea of things being useless and working hard on them is actually a very beautiful one. I do believe that part of the reason why museums of contemporary art are so incredibly popular right now, Tate Modern in London being the second most visited spot in all of the United Kingdom, is because it’s some of those only preserved and allowed spaces in our lives where things don’t have to do anything. You go to a place that’s clearly beautiful with stuff in it that clearly was difficult to do, but it doesn’t really have to do anything. I think there’s a particular gorgeousness in that.

My second favorite psychologist, well, he’s more than that. He works at Harvard. He’s a sociologist. Steven Pinker wrote a big piece of work over the last couple of years where he shows very clearly that violence has actually been going down worldwide steadily for 2,000 years, that every single century saw fewer deaths--he defines that by to die by the hand of another man--than the century before. Even the 20th Century with World War I, World II, the Holocaust in there, saw fewer people die--percentage-wise, that’s the only way you can look at it--than the 19th Century. The 19th Century saw fewer than the 18th, and so forth.

He shows that, among the Hulis, clearly a very colorful tribe in Papua, New Guinea, very close to Bali where I was, if you now live among the Hulis, the changes that you’re going to die by the hand of another man are seven times as high than if you live in Detroit, which is America’s most dangerous city. Basically, what he says and what I believe is that things are getting better. The civilization actually does work.

[Music]

Stefan: And so, we created this little film called Now is Better, and we can just let it go and turn the sound up.

[? And I have a wound that never will heal. And you are the one that constantly peels the skin away each and every day. Watch it bleed. Watch it bleed. Watch it bleed. And you have a mask that no one can see, but I have a way for seeing these things. But I have a way of seeing these things. The skin on your bones…. Pull it away, pull it away, pull it away. ?]

Stefan: So, summing up. What makes us happy? Many friends, good friends, a sense of accomplishment, nonrepetitive activities, religion, and--

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Clearly, you know what’s coming.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Can we have some light here? Can we all get up, please?

Audience: [Groans and laughter]

Stefan: So, this has been inspired by my sister, so blame my sister, who has joined a choir about five years ago. She says that she comes out elated from choir practice even if she hates the songs that are sung in choir practice. And, I brought you this whole thing. We’ll do this karaoke-style so that we all really sing the same lyrics. And, we’ll turn up the music, and we’ll go.

[Theatrical music]

Stefan: You know the song?

[Theatrical music]

Stefan: It’s a bit louder already. Okay.

All: All my clients drive me crazy, never show no guts at all. For the peanuts that they pay me, they get logos ten feet tall. Want to see three new directions for tomorrow’s drop dead line, picks the worst and mixes sections, we wind up with Frankenstein.

All my clients drive me crazy, never show no guts at all. For the peanuts, that the pay me, they get logos 10 feet tall. Stefan always shows the same stuff, seen it all on TED.com. New York clients are not that tough; he should work where I am from.

All my clients drive me crazy, never show no guts at all. For the peanuts, that the pay me, they get logos 10 feet tall.

Stefan: All right.

Audience: [Cheers and applause]

Stefan: That was actually pretty good, I have to say.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: We’ll do the bag test.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Number zeros: who feels like shit? Can we see some lights?

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: Twos: I’m pretty bad. Who is bored: number four? Sixers: things are okay? I feel good: number eight?

Audience member: Yes!

Stefan: All right. That’s about half. And, I love life: number ten?

Audience: [Cheers]

Stefan: Whoo-hoo!

Audience: Yay! [Laughter]

Stefan: Well, I have to admit that I think, ultimately, the chances that you’re going to become permanently happy from listening to me talk about happiness are about the same as the chances that you’re going to get skinny from watching me exercise.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: You ultimately would have to do these exercises or these techniques yourself. Of course, it’s not really practical that we would now all start a mass meditation in here. From the 20 minutes that we could possibly do that, there probably wouldn’t be much of an effect.

But, actually, you can do one thing. There is a scientist out there who I like a lot. His name is Matthew Seligman, and he sort of developed a technique that I’ve been doing for many months now and we’re actually working on some sort of app that incorporates this.

The technique is very, very simple. Before I go to bed at night, I write down three things that worked that day. I’ve been doing it yesterday. I’ve been doing it the day before. It takes an incredible little amount of time. Normally, I’m doing it on our prototype app. It looks a little bit better on the app, but it works just as nice in some little notebook. Three things, small and large, that worked that day, and clearly there is a lot of scientific background of why that would be a good idea. Obviously, the negativity bias being one big aspect of it that we naturally remember the things that didn’t work much longer, and it’s helpful to artificially remember stuff that actually did work.

Of course, you can say, “Well, all this happened, and stuff. It’s been too long. He’s been living in America for too long.”

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: You can go to The Happy Shop or the Happy Stop and take these happy pills.

Audience: [Laughter]

Stefan: If you really think it’s all bullshit, then you can always go and see this guy.

[Obnoxious laughing]

Stefan: Maybe we can get the sound up.

[obnoxious noises]

Male: When I am, I am relaxed. I am happy. I am relaxed. I am happy. I am relaxed. Boo-boo-boo-boo-boo-booooo.

Stefan: Thank you so very much.

Audience: [Applause]

Stefan: Thanks a lot.

Audience: [Applause]

Stefan: Thank you.

[Futuristic humming]

[Futuristic music]